UDON: A post mortem

2022-10-10 - 13 minutes

- Introduction

- About UDON

- Slow down

- Part Two

- Go fast

- The end?

- Update (December 2022)

- Update (April 2024)

Note: This is my first blog post, so be forgiving.

🔗Introduction

VRChat is a social VR platform built on Unity3D. Its users can upload their 3D assets, such as Avatars and Worlds. To provide interaction, a scripting language is provided. It’s called UDON.

When I was introduced to VRChat, I eventually got invited to learn the Japanese tile game Riichi Mahjong in the Chiitoitsu Parlor. The game is best played with three or four players. The table Prefab allows you to stack up players with CPU-controlled bots/NPCs (non-player characters).

Over time I got annoyed by the bad performance I had to endure while playing this game.

🔗About UDON

Udon is an interpreted bytecode language for client-sided functionality in VRChat Worlds. Each script is bound to an object where one player implicitly or explicitly takes ownership.

It consists of a fixed-size heap, a stack and nine variable-length instructions (4 or 8 bytes). These are as follows:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

| NOP | Nothing |

| PUSH | Pushes a heap index to the stack |

| POP | Removes the last index from the stack |

| JUMP_IF_FALSE | Jumps to a set instruction if the last value on the stack evaluates to false |

| JUMP | Jump to a set instruction |

| EXTERN | Call an exported function outside the VM |

| ANNOTATION | Prints a variable of the heap |

| JUMP_INDIRECT | Loads an index of the heap and jumps to this instruction |

| COPY | Copy one value of the heap to another index |

NOP, POP and ANNOTATION aren’t commonly used, so we are only left with six useful instructions.

The interpreter is implemented as a simple switch in a loop, as such

loop {

match code[pc] {

NOP => { /* ... */ }

PUSH { idx } => { stack.push(idx) }

POP => { stack.pop() }

/* ... */

}

}

Since you wouldn’t want to write assembly directly, you can choose higher-level languages and compilers.

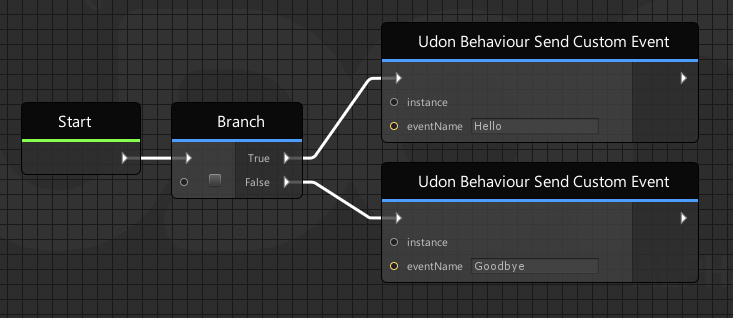

🔗Node Graphs

The VRChat team made this one. Unfortunately, it’s still very limited. Function calls and recursion are very clunky.

This caused the community to develop alternatives.

🔗UdonPieCompiler

from .UdonPie import *

def _start():

res = func(3, 23)

Debug.Log(Object(res))

def func(lhs: Int32, rhs: Int32) -> Int32:

lhs * rhs

This one uses a limited python language subset. Function calls are easy here but come with their own issues. For example, callable function signatures need to be manually updated, and python doesn’t integrate well into the Unity Editor.

🔗UdonSharp

public class SpinningCubes : UdonSharpBehaviour {

private void Update() {

transform.Rotate(Vector3.up, 1f);

}

}

Inspired by UdonPieCompiler, MerlinVR developed a C# compiler. Since traditional Unity scripting is done in this language, it fits well. In addition, most previous issues have been resolved, and even recursion is possible.

Merlin is also well known for releasing various tools to help VRChat world creators like USharpVideo, which uses UdonSharp. To this date, it is the most used compiler, and most shared assets require it. VRChat has since hired Merlin, who intends to improve UDON.

🔗Katsudon

An honourable mention goes to Katsudon, which I haven’t looked into enough.

🔗Slow down

However, all these are compiled down to the assembly language mentioned above. Six instructions isn’t a lot compared to other Virtual Machines. Java’s JVM currently has 203. Microsoft’s CIL, used by C#, has 229. Your CPU runs on over a thousand different instructions.

If you know any assembly language, you might wonder how basic arithmetic operations in UDON work.

🔗EXTERN

To get anything to happen, UDON code uses its sixth instruction to call into external functions. A simple float addition looks like this:

PUSH lhs

PUSH rhs

PUSH output

EXTERN "SystemSingle.__op_Addition__SystemSingle_SystemSingle__SystemSingle"

This is slow. How slow? In my testing, running against the same C# code running in a mono runtime, 200 times slower.

This might not be an issue for UDON’s intended use case, but the creative world moves on, and simple buttons and switches aren’t the only things around.

The Mahjong prefab we are using consists of over 6’000 lines of code and compiles to roughly 28’000 instructions. Of those, over 4’000 are EXTERN calls.

The slowdown caused by this is especially noticeable and irritating in VR.

🔗Part Two

This second part of the post is about my work and is more subjective. If you want to call it a day here, take this one lesson with you:

Don’t roll your own scripting language.

Use lua like everyone in the industry or web assembly, which seems very promising. Both are on the roadmap for ChilloutVR, another social VR platform.

🔗Go fast

To mitigate these issues, I had to come up with a solution. Or three. They are listed here in chronological order.

I went to work after obtaining a copy of the Mahjong table.

🔗Hooking

2021.06.05

If you aren’t familiar with this practice, hooking refers to a practice in modding where you insert a piece of code into the original code that branches into your code. Then, after your code executes, you can continue at the intended location or return, preventing the original code from running.

I could now wait for the VM to execute, check if I needed to intervene and run the heavy workload outside the slow UDON runtime. This helped mitigate the stutter issues I had with the Mahjong CPU.

The good:

- 100% compatibility: This worked fine in all tested Worlds that integrated the table. Luckily, world creators never adjusted this portion, and if they had, nobody would notice.

The bad:

- limited to specific segments: Since I could only intervene before the VM spun up, I had very rough control over what code I could replace.

- careful patches: The original script had to change a lot to make it compatible.

- couldn’t mitigate all slowdown: To preserve compatibility, I had to skip the first frame of the CPU’s turn, and only 13/14 lags were mitigated.

🔗Theseus ship

2021.08.09

The next battle strategy was to replace VM entirely. Calls to the VM would end up in native-run C# code. Luckily VRChat implemented the UDON VM in a set of interfaces, so I could set up a “fake” VM that implements this interface.

Sadly this didn’t work immediately as our modding framework didn’t support interfaces.

This requires going a bit deeper into the implementation side. As mentioned above, VRChat is a Unity3D game. Game logic is written in C# as it’s the primary scripting language of Unity. The default runtime is mono, a CIL interpreter and JIT.

Unity also provides an alternative compiler and runtime called il2cpp. IL refers to the bytecode language C# compiles to. il2cpp takes this bytecode language and converts it to C++, which is then again compiled to native machine code.

This allows Unity games to run on platforms where JIT compilation isn’t allowed, and interpreting is too slow. Another side effect is that the game becomes significantly harder to mod or reverse engineer.

In early 2020 VRChat switched to il2cpp, probably because of this exact side effect. With this change, modding, which previously injected CIL DLLs into the mono runtime, was on hold. Eventually, LavaGang developed a solution to make old mods work again with only minor adjustments. It consists of MelonLoader, which provides the known mono runtime, and Il2CppAssemblyUnhollower, which provides all the glue to work with the entirely different environment.

Through Il2CppAssemblyUnhollower, it’s possible to inject your CIL classes that are accessible from the il2cpp side. The shortcomings I had to face were in its “ClassInjector”, which I solved by forwarding information about implemented interfaces. Missing still were generic methods on interfaces, which UDON used for accessing heap variables.

🔗Generic Virtual

Looking into this made me curious.

Say you have a function GetValue<T>() on an interface I.

You might have multiple classes implementing I and multiple calls to I::GetValue<T>() with T being various types.

How does an ahead-of-time compiler know what code he should emit?

The solution il2cpp chose was to stamp out code for every possible combination of I and T, resulting in a gigantic pile of potentially unused code.

Lookups are done once at runtime and cached for performance reasons.

While the il2cpp compiler is proprietary, the Unity Editor provides its runtime library, as games have to link against it. Tracing down the callstack, I found a good place to hook into. When a generic method on an interface is first called, it will search through my injected classes and return those. Since we live in CIL mono, we can stamp out the needed functions at runtime.

You can find my patch to Il2CppAssemblyUnhollower here

Now I could finally hook up my own “fake” VM like so:

RegisterTypeInIl2CppWithInterfaces<FakeUdon.FakeUdonProgram>(true, typeof(IUdonProgram));

RegisterTypeInIl2CppWithInterfaces<FakeUdon.FakeUdonVM>(true, typeof(IUdonVM));

RegisterTypeInIl2CppWithInterfaces<FakeUdon.FakeUdonHeap>(true, typeof(IUdonHeap));

With this, no further changes to the Mahjong script had to be made. See for yourself:

In this video, you can see four tables with four Mahjong bots, each playing simultaneously. However, even with those all running, the game is perfectly playable if you can tolerate the noise.

The good:

- Massive Speedup: The Mahjong table execution is sped up by factor 200

- Generally applicable: Adding new scripts requires no changes to the code.

The bad:

- Huge initial effort: The initial investment was large

- Can’t adapt to small changes

I published all the glue code as a library in November 2021 here and let it rest.

At the end of December, I got messaged by Kitlith, who found the repository and was interested in speeding up Udon overall. He started recreating the VM in C# but could only get ~80% of the speed of the original code.

Through Advent of Code, I had recently learned Rust which I used to write an interpreter. Without any special optimization, it immediately surpassed the original VM by 5-15%. One particular benchmark (after applying some minor optimizations) was 30% faster.

Hey, I’m Kitlith. My original goal with C# was to emit .net bytecode and let the JIT built into .NET optimize it for us. I dove into the guts of mod<->game interaction to gain as much performance as possible, and was in the middle of reimplementing the UdonHeap when I got blindsided by Behemoth’s rust interpreter executing the benchmark we were using faster than just the time spent by my C# interpreter calling Udon EXTERNs. On the one hand, I was relieved, as that was a pile of hacks that was not going to be trivial to maintain, and I liked Rust anyway. On the other, there was now a new codebase that it took some time to get up to speed with.

The original C# code is still around, kept in the original branch if you’re interested in it, but it’s not very useful.

🔗JIT

A Just-in-Time compiler describes a runtime element that compiles code at runtime. Such compilers are found in most scripting languages, such as JavaScript, Ruby or Lua, and bytecode VMs like the JVM or mono.

The next attempt was to write a JIT compiler that converts UDON assembly into x86_64 machine code.

I wrote some code that took udon instructions as input, and did its best to combine them into smaller primitives. Behemoth took the output, and wrote code to emit x86_64 instructions. For example, if a program pushes 4 arguments, then immediately calls an extern that takes 4 arguments, then in theory we could emit a buffer that just contains all the arguments and pass that directly to the extern without bothering with pushing/popping the stack. We never got around to doing anything in the JIT besides immediately pushing all the arguments before calling the function, but the framework was there.

All in all, it wasn’t very complicated. No register allocation, very little optimization. There were some ideas on how to complicate it once we had control over the UdonHeap, but we weren’t there yet.

After writing the JIT, we measured its performance to be roughly the same as the interpreter, or slightly slower due to on-the-fly emitting. I wrote some code to emit as many blocks ahead of time as we reasonably could, and Behemoth extended that work so that blocks would directly jump between each other where possible. Measure the performance again and… it’s measurably faster than the interpreter, but only by a little bit.

At that point, I did some profiling. It turns out barely any time was being spent in any of the rust code we wrote, either the interpreter or the JIT. Most of the time was being spent calling out to udon EXTERNs, or dealing with the existing udon heap. There’s only so much we could do by only optimizing the core of the interpreter, if we wanted to get even faster, we were going to need to optimize everything else too. This is where our steam ran out. I wrote some code to try and extract the original functions for every udon EXTERN to try and reduce overhead there, and then never got around to integrating it with the interpreter/jit.

It may not have helped that our code was split between a bunch of branches that I wasn’t quite sure how to unify, so I just kinda… put it off. After all, it’s not like there was any rush, right?

At this point, I’ve mostly stopped playing VRChat and only rarely played Mahjong.

🔗The end?

On 2022.07.25, VRChat announced that they would ship the next version with Epic Games’ “Easy Anti-Cheat”. This would effectively prevent all of these efforts from ever working in-game again.

You can check out our code here

Special thanks to float3 for proofreading and spell checking this post.

🔗Update (December 2022)

VRChat announced in one of their recent blog posts “Udon 2”. They will transition to a WASM VM.

🔗Update (April 2024)

Merlin, the guy who was hired for “Udon 2”, recently got fired.

HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA

Screw VRChat