Fast JSON serialization in mono .NET/C#

2023-02-21 - 9 minutes

- Introduction

- Checking under the hood

- DOOM

- It doesn’t get better (Newtonsoft.Json)

- Let’s do it ourselves

- JIT to the rescue

🔗Introduction

After my last modding endevors in VRChat, Easy AntiCheat was added to it, breaking casual modding. This fiasco caused a lot of players to try the direct competitor, ChilloutVR which is developed by Alphablend Interactive (ABI).

Sadly to this date, no ingame scripting is offered there, so I have to complain about other things.

🔗Checking under the hood

ChilloutVR is based on the Unity3D Game engine, utilizing C#. Unlike it’s rival, the generated .NET intermediate language (IL) is not converted to C++, but runs on the dynamic runtime “mono”.

I attached an off-the-shelf .NET profiler and poked around. One aspect that peaked my interest was the ingame user interface.

Traditionally, a lot of Unity games utilize the builtin 2D tools to build interfaces. ABI chose the library “cohtml” by CoherentLabs.

As the name suggests, “cohtml” renderes an html page, like the webbrowser you are using right now. It utilizes the browser engine “Chromium” which powers Chrome and many other user agents.

The interesting part to me was, how Chillout got it’s internal state into this chromium instance. You could have probably guessed it from the title, it uses JSON. The important bits are collected in a struct, serialized and sent off to “cohtml”. There, it’s read by Javascript, which refreshes the UI. I won’t be looking at the Javascript part here, and instead, focus on the last part, before entering the Chrome domain.

From the C# side, they generate some nice structs somewhere…

[Serializable]

public class CVR_Menu_Data

{

public CVR_Menu_Data_Core core = new CVR_Menu_Data_Core();

/* ... */

}

[Serializable]

public class CVR_Menu_Data_Core

{

/* ... */

public int fps;

public int ping;

/* ... */

}

…they populate it with some current data…

CVR_MenuManager.Instance.coreData.core.ping = MetaPort.Instance.currentPing;

CVR_MenuManager.Instance.coreData.core.fps = (int)Mathf.Floor(1f / _deltaTime);

…and then send it off to “cohtml”:

public CVR_Menu_Data coreData = new CVR_Menu_Data();

public CohtmlView quickMenu;

/* ... */

private void SendCoreUpdate()

{

/* ... */

quickMenu.View.TriggerEvent("ReceiveCoreUpdate", JsonUtility.ToJson(coreData));

/* ... */

}

Perfect! Both .NET and C# are using UTF-16 for their string encoding so what could possibly go wrong.

There are endless different libraries for converting .NET objects to JSON. At the time of my investigation, ChilloutVR utilized a module that Unity shipped - “UnityEngine.JSONSerializeModule”. Parts of Unity’s C# source code is publicly available so let’s take a look at that.

namespace UnityEngine

{

[NativeHeader("Modules/JSONSerialize/Public/JsonUtility.bindings.h")]

public static class JsonUtility

{

[FreeFunction("ToJsonInternal", true)]

[ThreadSafe]

private static extern string ToJsonInternal([NotNull] object obj, bool prettyPrint);

public static string ToJson(object obj) { return ToJson(obj, false); }

public static string ToJson(object obj, bool prettyPrint)

{

if (obj == null)

return "";

/* ... */

return ToJsonInternal(obj, prettyPrint);

}

}

}

Besides a bug in it’s null handling, not a lot to see here.

Turns out, ToJsonInternal isn’t defined here, but in the Unity engine library UnityPlayer.dll, which is closed source and written in C++ so I won’t get to see pretty code.

Oh well… Let’s throw it into a decompiler and look at it anyway. I chose Ghidra here, because I’m already familiar with it. At least Unity provide developers with Symbol files so we get some nice function names.

Searching for the our Json converter we can find a call to mono that registers the function JsonUtility_CUSTOM_ToJsonInternal under the name UnityEngine.JsonUtility::ToJsonInternal.

Let’s follow it. It internally calls JSONUtility::SerializeObject, which eventually calls JSONWrite::OutputToString. That’s where the nice names end because now we get this beauty:

bool __cdecl Unity::rapidjson::GenericValue<

struct Unity::rapidjson::UTF8<char>,

class JSONAllocator

>::Accept<

class Unity::rapidjson::Writer<

class TempBufferWriter,

struct Unity::rapidjson::UTF8<char>,

struct Unity::rapidjson::UTF8<char>,

class JSONAllocator>

>(

class Unity::rapidjson::Writer<

class TempBufferWriter,

struct Unity::rapidjson::UTF8<char>,

struct Unity::rapidjson::UTF8<char>,

class JSONAllocator

> & __ptr64) const __ptr64

Quite a mouth full, isn’t it. C++ can be quite ugly with all namespaces and template parameters fully expanded. Let’s clean that up.

namespace Unity::rapidjson {

typedef GenericValue<UTF8<>, JSONAllocator> SomeValue;

typedef Writer<TempBufferWriter, UTF8<>, UTF8<>, JSONAllocator> SomeWriter;

template <typename Handler>

bool Accept(Handler& handler) const;

}

That solves the mystery. Unity utilizes rapidjson, a widely known json library, built by Tencent. We can find it’s source code and this function Accept too.

But wait: It says UTF8 there.

A few paragraphs up we noted that both .NET and Javascript use UTF-16.

What’s going on here?

Nope! It totally can. Besides that, it supports different endianess, UTF-32, ASCII and your own encoding if you are willing to write implement it’s trait.

After serializing the object, we return again, convert our new UTF-8 string back to UTF-16 and pass it to the mono domain.

From there, the string is forwarded to cohtml which - once again - converts it to UTF-8 and finally passes it to v8, Googles Javascript engine, which may or may not convert it back to UTF-16.

So let’s recap what’s going on by looking at a single .NET System.String object.

UTF-16 (.NET) -> UTF-8 (Unity) -> UTF-16 (.NET) -> UTF-8 (v8) -> UTF-16 (Javascript)

Ok. Let’s all take a breath. This is pretty stupid but who cares about a few microseconds here and there. I remember a Canadian Professor, who’s library can convert gigabytes of UTF in split seconds thanks to clever SIMD instructions. Didn’t he also write a cool SIMD accelerated JSON library?

Let’s see how rapidjson fares here. Can it make up for all the time we wasted converting strings?

🔗DOOM

Starting from the top of Accept. First rapidjson:

switch(GetType()) {

case kNullType: return handler.Null();

case kFalseType: return handler.Bool(false);

case kTrueType: return handler.Bool(true);

Let’s check back on Unity

switch(uVar16 & 0xff) {

SomeWriter::PrettyPrefix(param_1,0x80000000);

bVar8 = SomeWriter::WriteNull(param_1);

case 1:

SomeWriter::Prefix(param_1,0x80000000);

bVar8 = SomeWriter::WriteBool(param_1,false);

break;

case 2:

SomeWriter::Prefix(param_1,0x80000000);

bVar8 = SomeWriter::WriteBool(param_1,true);

break;

Close enough. Let’s look inside WriteNull. Rapidjson again:

bool WriteNull() {

PutReserve(*os_, 4);

PutUnsafe(*os_, 'n'); PutUnsafe(*os_, 'u'); PutUnsafe(*os_, 'l'); PutUnsafe(*os_, 'l'); return true;

}

Sure sure. Make sure you can write four characters and then just dump them. Let’s check on Unity.

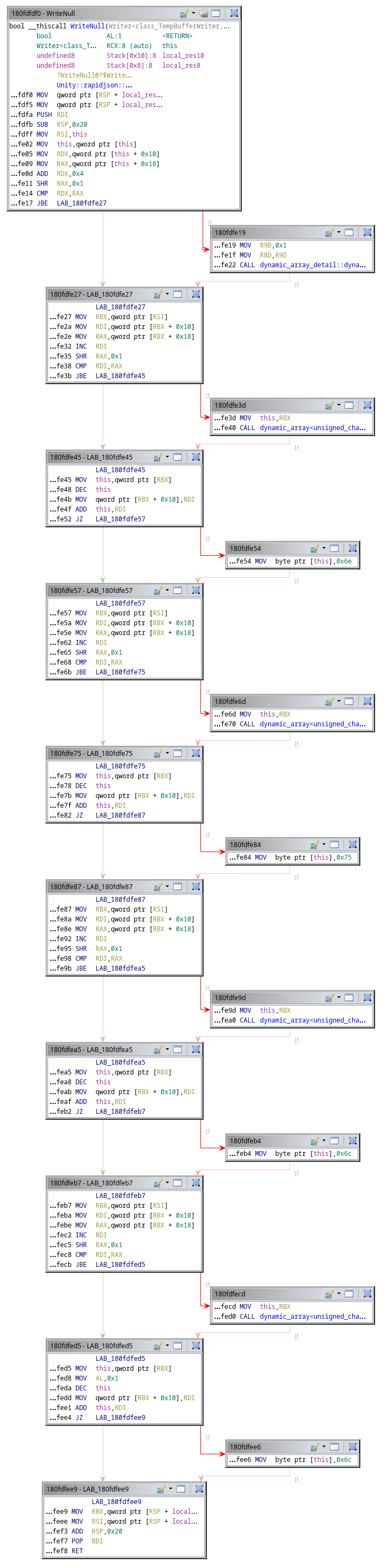

Uhm… What exactly is going on here? If you got strong guts, check out the full decompilation of WriteBool and it’s assembly.

Let’s clean the decompilation up a bit.

bool SomeWriter::WriteNull(SomeWriter *this)

{

dynamic_array<unsigned_char, 0> *vector = this->backing;

if (vector->capacity < vector->length + 4U)

dynamic_array_detail::dynamic_array_data::reserve(vector, vector->length + 4U, 1, 1);

if (vector->capacity < vector->length + 1)

dynamic_array<unsigned_char, 0>::grow(vector);

vector->data[vector->length++] = 'n';

if (vector->capacity < vector->length + 1)

dynamic_array<unsigned_char, 0>::grow(vector);

vector->data[vector->length++] = 'u';

if (vector->capacity < vector->length + 1)

dynamic_array<unsigned_char, 0>::grow(vector);

vector->data[vector->length++] = 'l';

if (vector->capacity < vector->length + 1)

dynamic_array<unsigned_char, 0>::grow(vector);

vector->data[vector->length++] = 'l';

return true;

}

All the other functions look the same Prefix, WriteBool

PutReserve -> dynamic_array_data::reserve sure.

Why are there bound checks for the rest? PutUnsafe sounds pretty clear to me.

We already ensured there is enough space.

I couldn’t even express the extra null checks that are entirely non-sensical.

Let’s check what rapidjson usually does.

That’s better. So it turns out Unity just used the library wrong. I’ve tried contacting them about this half a year ago and didn’t hear back. This is still an issue in the latest version.

🔗It doesn’t get better (Newtonsoft.Json)

After ranting about my findings in some places, my words must have somehow gotten through to the ChilloutVR developers.

“Don’t despair” someone thought, and replaced the call to UnityEngine.JsonUtility.ToJson with Newtonsoft.Json.JsonConvert.SerializeObject.

Since Newtonsoft is written in C#, we get rid of one layer. Naturally it’s slower than Unity’s serializer.

Oh yeah maybe let’s not read these thousands of lines of corperate OOP garbage code and inspect the output instead. Since we are a Unity Game, Vector3 is probably interesting.

{

"x": -0.108,

"y": 0.082,

"z": 0.215,

"normalized": {

"x": -0.424877554,

"y": 0.3225922,

"z": 0.845821,

"normalized": {

"x": -0.424877584,

"y": 0.322592229,

"z": 0.8458211,

"magnitude": 1.0,

"sqrMagnitude": 1.0

},

"magnitude": 0.99999994,

"sqrMagnitude": 0.9999999

},

"magnitude": 0.2541909,

"sqrMagnitude": 0.064613

}

Uuuuuuh… Where do these two nested Vectors come from? This prints 12 as floats are four bytes and we have three of them.

Debug.Log(System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.SizeOf(UnityEngine.Vector3));

Let’s first look at the implementation again.

namespace UnityEngine

{

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public partial struct Vector3 : IEquatable<Vector3>, IFormattable

{

// X component of the vector.

public float x;

// Y component of the vector.

public float y;

// Z component of the vector.

public float z;

Sure, sure. Aditionally it implements some more constructors, utility functions and aritmetic operators.

// Returns this vector with a ::ref::magnitude of 1 (RO).

public Vector3 normalized

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptionsEx.AggressiveInlining)]

get { return Vector3.Normalize(this); }

}

/* ... */

// Returns the length of this vector (RO).

public float magnitude

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptionsEx.AggressiveInlining)]

get { return (float)Math.Sqrt(x * x + y * y + z * z); }

}

/* ... */

// Returns the squared length of this vector (RO).

public float sqrMagnitude { [MethodImpl(MethodImplOptionsEx.AggressiveInlining)] get { return x * x + y * y + z * z; } }

Oh… Two readonly properties. Every time a Vector3 get serialized by Newtonsoft, these values are created out of thin air. Why in gods name would you want that?

Interesting too; since normalized returns another Vector3, it serializes that one too, which creates another one in normalized which starts over again…

and then stops?

Apparently, Newtonsoft.JSON checks objects against all their parents to check for eqality and the first normalization iteration wasn’t normalized enough (“magnitude”: 0.99999994).

This behavior is called ReferenceLoopHandling.Ignore and can be disabled.

Not the part where it serializes properties, the part where it checks for recursions.

The default behavior, of course, in good old C# fasion, is to just throw an exception.

🔗Let’s do it ourselves

Once again I’m looking at attrocious implementations and I’m thinking to myself how I’d do better. I was playing around with a few approaches. My requirements were:

🔗minimal runtime cost

It should be fast on consecutive calls. The first call, during game launch, can be slow as the gameplay isn’t interrupted.

🔗avoid allocations

It would be great if we don’t have to track memory across multiple domains. The size should be very predictable anyway.

🔗version agnostic

I’m just modding the game, therefore I’m out of the games development loop and I don’t want to annoy users to constantly update their mods. This means, that I can’t hardcode the games structs. So we have to resort to generic runtime serializer code. Or do we?

🔗JIT to the rescue

After many considerations, I eventually settled on writing another JIT.

I’ve only shot myself in the foot 20 times or so as the kind folks on the ChilloutVR modding server can attest.

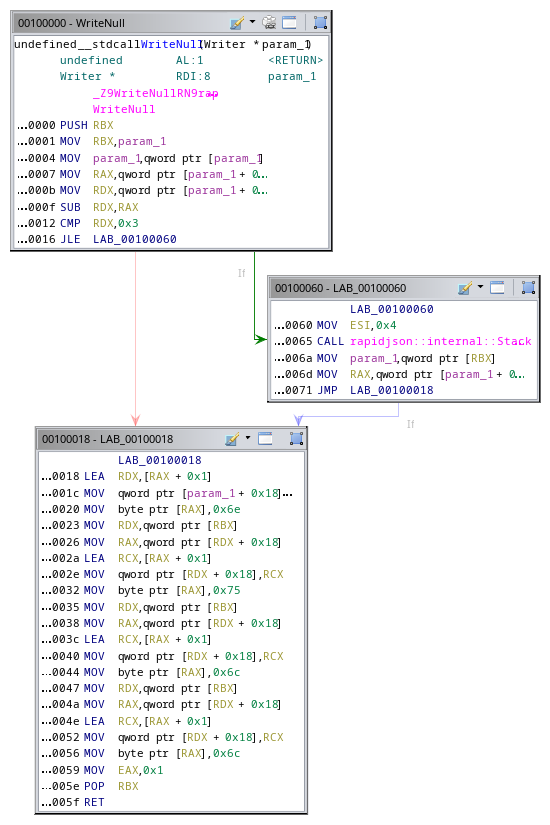

The JIT works as follows: Pass an instance of the object to an introspect function. This function inspects the type definition of the target type recursively and emits x86_64 assembly, which writes to a string buffer parameter. Since the target size can’t be know ahead of time, we determine the target size in another emitted function and resize our buffer if it’s not big enough.

Text that is known ahead of time is converted to encoded mov instructions.

Using our example from above, serializing a snippit like {"core":{"fps":120,"ping":10}}:

# Writing `{"core":{"fps":`

mov rdx, 0x3A2265726F63227B # {"core":

mov [r14], rdx

mov [r14 + 8], 0x7066227B # {"fp

mov [r14 + 12], 0x2273 # s"

mov [r14 + 14], 0x3A # :

add r14, 15

To serialize numbers, I’ve decided to use the external Rust library itoa for integers and ryu for floats. Jumping out of our assembly code into compiled code, we have to respect calling conventions. I’ve chosen the sysv64 calling convention and a jumppad function looks like this:

pub unsafe extern "sysv64" fn push_f32(value: f32, dst: *mut u8) -> usize {

ryu::raw::format32(value, dst)

}

A detailed description of the calling convention can be found on osdev or wikipedia. The important bits are: “Parameters to functions are passed in the registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9”, floating point arguments XMM0-XMM7, “Integer return values up to 64 bits in size are stored in RAX”.

# load float from our object at an offset

movsd xmm0, [r15 + 0x12]

# pointer to our buffer

mov rdi, r14

# load the address to the serializer function

mov rdx, @push_f64

call rdx

# advance target address

add r14, rax

A type we can easily serialize ourself is bool. We can test the value in assembly and conditionally emit writing “true” or “false”.

# load bool and check the value

mov dl, [r15 + 0x16]

test dl, dl

je emit_false

# Write "true"

mov [r14], 0x65757274

add r14, 0x4

jmp exit

emit_false:

# Write "false"

mov [r14], 0x65736C6166

add r14, 0x5

exit:

The implementations for other types aren’t particularily novel and therefore omitted from this blog post. You can find the full implementation and example usage code here.

🔗Performance

I’ve been very happy with the performance of this implementation. The main contributing factor certainly is the fact that we don’t allocate a bunch of memory every frame. This speeds up serialization and also helps with garbage collection stalls.

🔗Limitations

This implementation can only serialize types by their field members, certain trivial value types and a limited subset of language classes. Complex serializer implementations won’t be respected.